Access: How a St. Louis Nonprofit Guides Kids from Middle School to College

Operating out of three Catholic middle schools, Access Academies offers enrichment, counseling, and scholarships to hundreds of disadvantaged kids.

This story first appeared on The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

The jump from eighth grade to high school is one of the hardest transitions in childhood. Joseph Olascoaga had to make it while living thousands of miles from his parents.

His mother and father, who immigrated illegally to St. Louis before he was born, returned to Mexico when he was still in middle school. It was a necessary step — back in their hometown, Joseph’s grandmother was homebound and badly in need of care — but it left him alone with the choice of where to enroll after he graduated from Saint Cecilia School and Academy, the Hispanic-majority Catholic school he’d attended since his elementary years.

He moved in with his older sister and brother-in-law, who were happy to drive him to school interviews and open houses. Yet he was still faced with the complexity of the city’s sprawling Catholic education sector, which serves thousands of families as an alternative to the chronically struggling St. Louis public school district.

Each choice bore a heady price tag and an unfamiliar name: Christian Brothers College High School, Chaminade College Preparatory School, St. John Vianney High School. “I had no idea what high school to go to,” Joseph remembered. “I didn’t even know all these schools existed.”

Fortunately, he’d been dealt a trump card before the process even began. Beginning in sixth grade, Joseph participated in Access Academies, a nonprofit initiative that provides hundreds of St. Louis-area students with after-school activities, high school and postsecondary counseling and financial assistance. Embedded in three Catholic middle schools, including St. Cecilia’s, Access Academies staffers help families send their children to the schools they want and make sure they stay on track to succeed after graduation. In total, the program has awarded $9 million in scholarships since its founding in 2005.

Perhaps more importantly, it offers a model of intensive support that bolsters local institutions while helping profoundly disadvantaged children transition to adulthood. Across St. Louis, 37 percent of children live below the poverty line — more than double the national average — while fewer than one-quarter of all K–12 students can read or do math at grade level. In a city that has been fiercely criticized for not helping young people to thrive, the aid provided by Access Academies allows families to choose their next steps without having to decamp for the suburbs.

Participating students — about 500 currently, distributed among middle schools, high schools, and universities — receive benefits ranging from tutoring to summer academies to care packages in their college dorms. And to a large extent, they’ve been successful, with 97 percent of Access Academies students graduating high school on time;93 percent are accepted to a post-secondary institution.

Above all, said Shelly Williams, Access Academies’ executive director, they get the chance to see the possibilities that await them outside their neighborhoods and nearby schools.

“A lot of our kids simply don’t have that opportunity, whether they’re in charter or public schools,” Williams said. Whether or not a student happens to live in one of St. Louis’s prosperous neighborhoods is “sort of the indicator of whether you have access to opportunity,” she added.

Joseph is now a freshman at Saint Louis University, deciding between majoring in business or engineering. Five years after his largely self-directed high school search, he said the organization laid a path to his success in college and beyond.

“Access was feeding me information, like: ‘This high school is good, this high school is also good. What’s the difference between both of them?’ And it wasn’t ever a financial problem because they could help me.”

Staying ‘10 steps ahead’

Many St. Louis parents are just as daunted by the high school and college application processes as Joseph was in eighth grade.

The local K–12 menu is overstuffed with options, including traditional neighborhood schools, charters and a few highly regarded magnet programs. To make things even more complicated, St. Louis is home to one of the largest Catholic school sectors in the country — the city was founded by French settlers and named after a Catholic saint — and for over a century, the Archdiocese of St. Louis has enrolled tens of thousands of pupils in both the city and surrounding St. Louis County.

Families historically opted for private or parochial schools out of necessity as well as religious devotion. St. Louis Public Schools has long been one of the most troubled school systems in the country, routinely posting dreadful standardized test scores even before the learning catastrophe of COVID-19. In just over 50 years, the district lost 85 percent of its students, and the vast majority of those left are poor.

But the cost of going private can be prohibitive. Annual tuition at the highly regarded (and secular) John Burroughs School, which produced Mad Men star Jon Hamm and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, approaches $35,000. The comparatively cheap Nerinx Hall, a Catholic girls school in suburban Webster Groves, still costs over $18,000 to attend this year.

Access Academies offers substantial financial aid to participating families, paying nearly $750,000 in high school scholarships and secondary costs (application, uniform, and technology fees can also be steep) last year. The organization also works directly with high schools to negotiate discounts for families that still struggle with the bill.

But Williams said that logistical help can be no less crucial, especially as students begin to survey their prospects after high school. The procedural obstacles woven into the college search, including arranging campus visits and wrangling tax documents to complete financial aid forms, prevent thousands of potential freshmen from enrolling in college every year.

“It’s layers and layers of things, and there needs to be someone here to help them navigate those layers and stay on top of the laws, which are constantly changing,” Williams said, noting that the federal financial aid form has undergone significant changes this year. “We have to stay 10 steps ahead of all the systems, try to prepare our families in the meantime and be emotionally supportive too.”

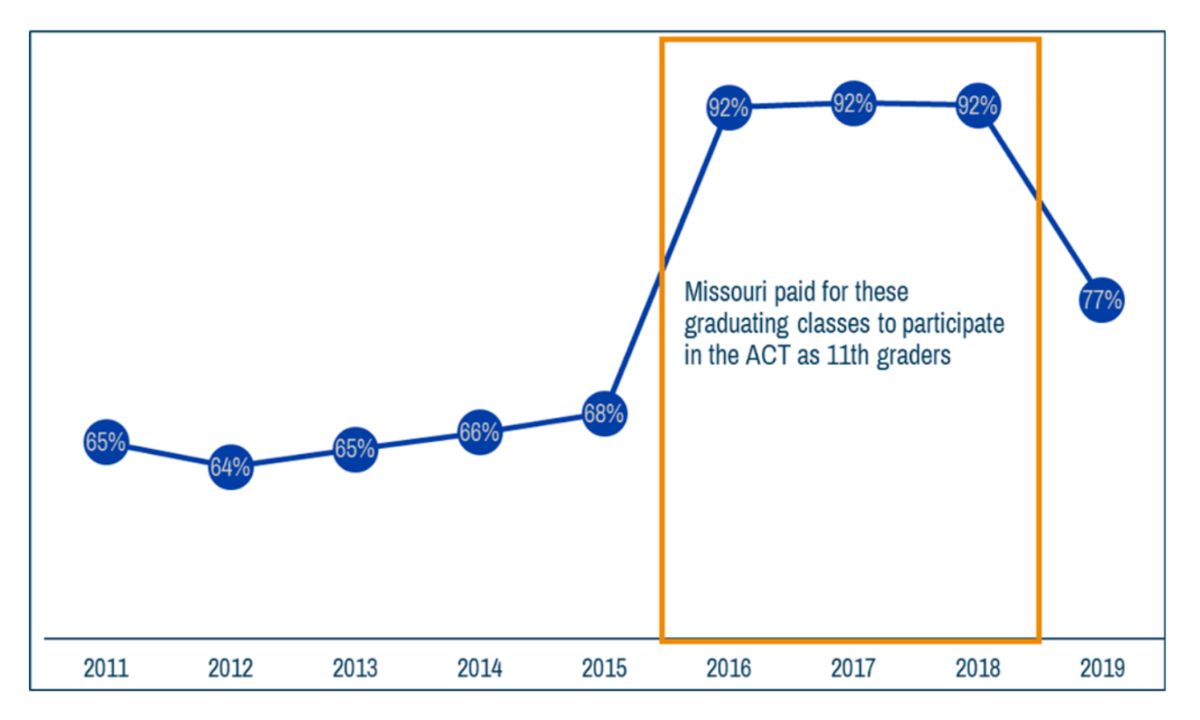

Both raw application numbers and public opinion polling show that interest in college has declined somewhat since the pandemic, but in Missouri, the trend seems to go back a decade or more. According to a 2022 brief from Saint Louis University’s Policy Research in Missouri Education Center, the rate of Missourians immediately enrolling in either a two- or four-year college after graduating high school fell from 69 percent in 2011 to 62 percent in 2019. When then-Gov. Eric Greitens eliminated state funding for high school juniors to sit for the ACT, the rate of students taking that exam fell by 15 percentage points.

Access Academies requires its students to take the ACT and provides a free preparatory course on Saturday mornings. It also hosts bilingual seminars on how to fill out financial aid forms (dubbed “FAFSA Frenzies”) and pushes students to identify schools or vocational programs that interest them in their early high school years.

The strategy is specifically tailored for the kids served by Access. Carolyn Dubuque, the organization’s director of mission effectiveness, said that many of the private schools in the area expect students to take the initiative in contacting their college offices. But students like Joseph, who was a starting forward on his high school soccer team, helped look after five nieces and nephews, and worked a construction job in his senior year, may not be prepared to do that.

“You can’t spit in St. Louis and not hit a Catholic high school,” Dubuque observed. “But these Catholic high schools are not designed for our kids — underserved, first-generation students.”

Each Access Academies middle school (St. Cecilia’s and St. Louis Catholic Academy in St. Louis proper, as well as Sister Thea Bowman Catholic School in East St. Louis, Illinois) is staffed with graduate support directors who follow all of the program’s students throughout their time in high school. If the students wish to, they may continue to receive services — including counseling and “micro-scholarships” tied to GPA and career benchmarks — while enrolled in college.

Amy Clark, Access’s director of college and career initiatives, said that her job often involved cajoling high schoolers and their parents to keep working through a nasty labyrinth of paperwork and email portals.

“A lot of the help isn’t us making magic happen,” Clark said. “It’s: ‘Open up your email with me, and let’s go through this. Don’t be overwhelmed with this form, let’s just get it submitted.’”

‘Engaging with an existing community’

Admissions essays and summer internships seem like distant concepts at Sister Thea Bowman Catholic School.

In part, that’s because of its setting. East St. Louis, which looks out at the hopeful curve of the Gateway Arch from just across the Mississippi River, is one of America’s poorest and most crime-plagued communities. The most recent state accountability report issued by Illinois shows that just 13 percent of the local school district’s students scored proficient in reading in 2023, while less than 6 percent scored proficient in math.

Situated on a quiet stretch of the aptly named Church Lane, the school exudes a placid feel. On a Thursday afternoon just before Thanksgiving, the walls were bedecked with pictures of prominent Catholics, including that of Sister Thea herself, a charismatic nun who evangelized to African Americans through music and dance. The building recently finished a multi-year effort to install soundproof windows that, according to the school’s advancement director, could withstand a chunk of asphalt being dropped on them — which is exactly what happened nearly 10 years ago to the ones they replaced.

At 3:00, neat lines of kindergartners and elementary schoolers trooped homeward for the day. Once they left, middle schoolers poured into their after-school activities, and the hallways began to echo with the sounds of music lessons and word problems.

Access Academies’ contact with students begins with supplementary offerings for sixth and seventh graders, who choose among dozens of enrichment programs including cooking, public speaking, robotics and sewing. Eighth graders are increasingly steered toward researching and applying to high schools, but they are also free to take part.

In one classroom, Sara Mullins, a volunteer with the local nonprofit Pianos for People, gently worked with eight pupils as they plinked on electronic keyboards. Down the hall, Sister Thea Bowman alumnus Paris Grimmett walked a larger group through the differences between checking and savings accounts as part of his personal finance education program, First Generation. Annamary King, a math instructor who also offers free tutoring to high schoolers struggling at their next destination, explained triangular numbers to her math club, the PI-thons.

“When the sixth graders realize they’re going to be staying until five o’clock, their reaction is, ‘Do we really have to do this?’” said Mary McGeathy, the school’s former principal and a current reading instructor. “But when they get into it, there are very few complaints.”

Enrollment in St. Louis-area Catholic schools has eroded by tens of thousands of students over the last two decades, and after multiple closures, Sister Thea Bowman is the last one remaining in East St. Louis. Its student body, which hovered around 80 in the early 2000s, numbers more than 100 today, even after COVID dealt a nasty blow to the Catholic sector nationwide.

Williams, the Access Academies executive director, said that the original aim of the organization was to put down roots in established schools that might otherwise be vulnerable, rather than presenting local communities with a potted reform.

“The idea was to strengthen the communities where they were instead of creating anew,” Williams said. “If you’re engaging with an existing community and listening to what they’re saying, people will absorb and participate in that differently.”

The school’s partnership with Access Academies has helped attract and retain families who might have otherwise slipped away. Along with the cost-free enrichment and mentoring, middle schoolers have become eligible for scholarships that will allow them to continue attending private schools after they graduate — a major attraction for parents. In prior years, eighth graders largely matriculated either to the local public high school or a handful of other Catholic alternatives in nearby Belleville and Waterloo. Now a sizable majority cross the river to attend schools in Missouri, even if they have to take multiple buses to commute.

Carmelita Spencer, a former math and science teacher at Sister Thea Bowman, now works as the school’s Access Academies graduate support director. A proud native of East St. Louis, she nevertheless harbored hopes that the availability of scholarships and counseling would open students’ minds to the possibility of attending school somewhere other than their hometown.

Now she spends most days on the road, crisscrossing between high schools to arrange meetings with her students and their teachers. The constant driving puts more miles on her car — an old loaner from her sister — but she relishes the chance to advocate for her old elementary schoolers.

“I know my students’ abilities, so it’s easier for me to advocate for them when it’s time for them to go to high school,” Spencer said. “I have students who struggle, and I’m able to go the school and say, ‘We need to put special support in place for this student.’”

Making ‘that dream come true’

In some ways, Remy and Giovanni Valenzuela need less than the typical Access Academies student in the way of special support. For one thing, they’ve got each other to lean on.

The brothers are both seniors at St. Mary’s High School, just a few minutes from their home in South St. Louis. The school has served local families as a neighborhood institution for the better part of a century; Hall of Fame catcher Yogi Berra, the son of Italian immigrants, attended in the 1930s.

Remy and Gio are succeeding in their classes while juggling evening shifts as a dishwasher and line cook at a local Olive Garden. They are also making plans to attend college this fall — acceptance letters have arrived from Central Michigan University and the University of Wyoming, as well as local options Maryville University and Fontbonne University — and have long planned to join the Army or Marines, following a path traveled by their parents, grandfathers and a slew of cousins.

But even while crediting their own diligence and attentive parents, both acknowledge that they might not be in the same enviable position without the help of Access Academies. The boys only moved to St. Cecilia’s in second grade after Remy, the older brother by a year, struggled to pick up math at a well-regarded magnet school. Their mother, Kim, worried that his academic needs wouldn’t be met without more support and smaller class sizes.

During their time in middle and high school, the brothers took advantage of the benefits available to all Access students: afterschool enrichment, financial aid, admissions counseling, and multiple practice runs at the ACT (which Gio credits with lifting his score from 18 to 25 out of a possible 36). But their graduate support directors also pushed them to enjoy the aspects of high school that make the hard work worthwhile.

“I wrestled and lost a ton of weight because of it,” Gio said. “I became the secretary of the National Honors Society this year. Access was willing to help pay for my clubs and my college-credit classes. And they were able to take the strain off our parents so that we could actually enjoy our time in high school.”

Kim Valenzuela is spread thin as a mother, nurse and occasional caregiver to her husband’s parents, who live with the family. She said the years of assistance provided by Access gave her the assurance that her sons would find their way in a city where too many young men fail to reach college or a productive career.

A recent parent meeting took her back to St. Cecilia’s, where she sat in a room covered in the names of Access students and the high schools they wished to attend. On one wall were Remy and Gio’s names and their hoped-for destination, St. Mary’s, which they’d scrawled as sixth graders. Kim said the ritual, and the memory it evoked of her sons as pre-teens, encapsulated what the program helps families like hers achieve.

“They want to know what your plan is for high school and college,” she said. “You lay this plan out, and they help you make that dream come true.”

Kevin Mahnken is a senior writer at The 74.

@KevinMahnken | [email protected]